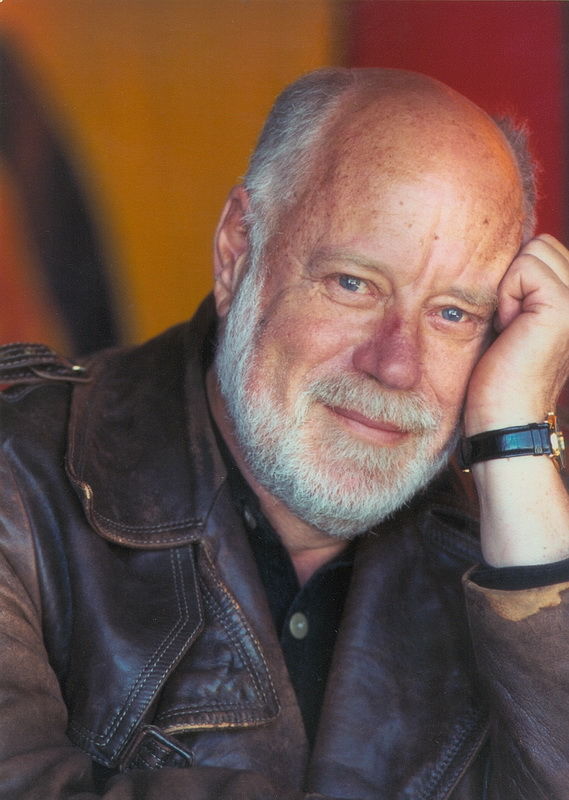

Phillip Adams

| Phillip AdamsBio: Phillip Adams is a writer, journalist, public broadcaster and the father of a child in a public school. School ties that bindWhile it looked like someone had shoved a stick into a community of termites, the mound was the Sydney Opera House and the over excited insects were children. Countless kids, a jostling, joking jumble of pre-adolescence bussed in from all over the state. A jetsam of genders, races and religions gloriously misbehaving though some looked wide-eyed with terror at what lay ahead. Because, seconds later, this cacophony of kids was expected to file inside and become a mass choir. While others would form a symphony orchestra or a jazz band or a corps de ballet. It was one of five similar events organised (if this chaos could be called organised) by the Arts Unit of Public Education NSW. What used to be known as the state schools. The best part of 1,000 kids who’d never been together before, only rehearsing in tiny groups in their scores of separate schools scattered all over the map. It would take a miracle for this mess to meld into a choir that, by definition, requires discipline, cohesion and sublimation of the ego. And the miracle occurred, right up there with the parting of the Red Sea. Suddenly the kids were sitting uietly in a vast horseshoe around the stage – singing to a standing-room-only audience of adoring parents. Like us, there to applaud our 11-year-old, along with the bus load of her friends from Scone Primary. It was an enchanting night and I’d like to give a standing ovation to all the grown-ups involved – to the composers, choreographers and conductors who put the epic together and to the umpteen teachers who prepared their kids, these tiles in a musical mosaic. One of the reasons I found it so moving, so marvellous, was because it symbolised what used to be the miracle of Australia’s public education system. Now so dumped on, derided and demonised by ideological critics. With teachers constantly fighting demoralisation and inexorably diminishing funds. The public school system takes all comers. The disabled, the children of the long-term unemployed. Disturbed kids from dysfunctional or drug addicted families. The classes are crowded with kids of all classes, and kids of any colour can wear the school colours. Whereas, in essence, the private school system is about exclusion, privilege, religious or caste definition. There’s no denying that many of the best schools in the country are private schools – how could it be otherwise? But whatever can be said in their favour, they are tribal and socially divisive. John Ralston Saul describes public education as “the single most important element in the maintenance of a democratic system”. He’s right to stress that the better the citizenry as a whole are educated, the wider and more sensible public participation, debate and social mobility will be. Consequently, the accelerating drift to private education, whether in Saul’s Canada or our Australia, siphons off the elites until the energy and economics of the public system is destroyed. “That a private system may be able to offer a limited number of students the finest education in the world is irrelevant,” he writes. “Highly sophisticated elites are the easiest and least original thing a society can produce. The most difficult and most valuable is a well educated populace.” Throughout the western world, the wealthiest are the healthiest. People who control their lives have infinitely better health outcomes than those who don’t. The war on Medicare will produce a two- and three-tier system where the affluent can jump queues and access the best of everything whilst the mass of society will be queuing for public wards that, increasingly, are pauperised. The same process is accelerating the decline of public education whilst the private system enjoys increasing subsidies. Thus the criticisms of public education are self fulfilling – and any short-term benefits enjoyed by the kids at private schools will be undermined by what we already see across the Western democracies. As Ralston Saul says, “Having made such a central contribution to the rise of democracy, nations like the United States and England have ever greater difficulty in making their systems work.” What we saw at the Opera House was the system working at its best. Turning social chaos into creative harmony and teaching kids from every imaginable background how to get on with each other. And, yes, teaching them that life is about dealing with difference, with conflict and abrasions, rather than being placed in ghettos of parental choice, where they’re coddled or quarantined – not to mention indoctrinated in denominational or demographic terms. “We could do worse than reduce classes from the typical 20 to 30 students down to 10,” writes Saul. “This would mean hiring more teachers when public budgets tell us there’s no available money. A more important point is that there’ll be even less money in a society of functionally illiterate citizens.” The conclusion of our Conservative politicians? “That we cannot afford to educate properly our citizenry. We know this is a suicidal and lunatic policy position. What we are doing, therefore, is passively accepting the conclusion of lunatics.” If you visit a school like Scone Public, you won’t see deterioration or disintegration. You will see a well run, happy and attractive school with a dedicated principal and some fine teachers. Yet all through our district there are people who damn near bankrupt themselves so that their kids can go to private schools. In opting out of the state system, such parents are part of a process that will, down the track, damage everyone. Including the most privileged. A modern democracy is a complex thing, made up of differences that have to be tolerated and, where possible, celebrated. By separating kids into schools based on exclusion, no matter how loftily that exclusion is expressed, is to place democracy in jeopardy. Despite all our differences, we have to learn to sing the same songs. We have to learn to sing in tune and in harmony. |